Welcome back to another edition of the Ultimate Fitness series!

After discussing flexibility training last time, today’s focus is on speed and the optimal ways to train for it.

As one of my coaches wisely stated, “There has never been an athlete who was just too fast.”

Speed is a quality worth continually enhancing as it plays a crucial role in nearly all sports.

It’s often considered a fundamental aspect of athleticism.

With that in mind, let’s dive right in!

Definitional Basics

Let’s begin by defining what speed truly entails.

Speed can be defined as the capacity to respond or act swiftly under conditions free from fatigue.

As previously noted, it serves as a fundamental requirement for success across a spectrum of sports.

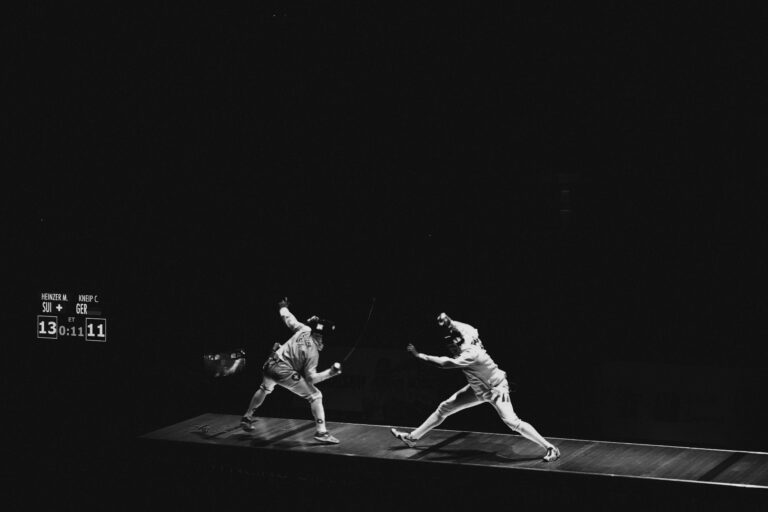

For instance, the demand for speed manifests in various scenarios: the need for quick decision-making in fencing, the urgency of time constraints in sprinting, or the necessity for precision in long jump.

Within the realm of motor skills, speed is grouped among the conditional abilities, alongside endurance and strength.

Nevertheless, it remains a subject of theoretical debate, making its categorization somewhat ambiguous.

For instance, some theorists classify speed as a subset of strength.

In practical terms, however, it proves beneficial to view and cultivate speed as an autonomous skill.

Speed can be dissected into two components: reaction speed and movement speed.

Reaction speed pertains to the aptitude for promptly responding to stimuli or information.

This can involve either a simple reaction to a familiar signal with a predetermined action or a choice reaction to an unfamiliar signal necessitating a decision.

In a simple reaction scenario, the nature of the information processed varies depending on the sport.

It could be visual, as seen in motor racing, fencing, or boxing; auditory, as experienced at the start of a sprint; tactile, as encountered in wrestling or judo; or kinesthetic, as observed in gymnastics or diving.

Regardless of the mode of information reception, the phases of reaction time remain consistent:

- Excitation occurs at the receptor, such as the ear or eye.

- This excitation is then transmitted to the central nervous system.

- A motor signal is generated and initiated.

- This signal is transmitted from the central nervous system to the muscles.

- Finally, muscle stimulation leads to mechanical activity.

Reaction times fluctuate depending on the modality through which information is received.

The speed of choice reaction is influenced by several factors:

- Training age

- Competition experience

- Biological age

- The specific limb involved in the movement

- The complexity of the information

- The skill level of the opponent

Choice reaction speed can take two forms: acyclical, as seen in a drop jump, or cyclical, as in a sprint.

The sprint serves as an illustrative example to elucidate the phases of cyclical speed reactions:

- In the initial phase, reaction speed is highly important.

- Subsequently, the ability to accelerate becomes crucial.

- This is followed by the attainment of maximum speed.

- Finally, the focus shifts to maintaining maximum speed.

In conjunction with speed, it’s imperative to mention action speed, which denotes a sport-specific and multifaceted ability of an athlete to act swiftly and effectively.

This ability is contingent upon the athlete’s coordination, physical prowess, mental acuity, technical proficiency, and tactical understanding.

Diagnostic Assessment of Speed

Speed can be evaluated using various testing methodologies. While it’s impractical to delve into every single test, it’s worth noting that distinct tests exist for each component of speed, each with its own set of advantages and limitations.

Speed Training

The cornerstone of speed training lies in high-intensity efforts.

Prior to engaging in such training, thorough preparation of the muscles is essential, necessitating a comprehensive warm-up routine.

Achieving optimal activation of the central nervous system is paramount, which can be facilitated through both targeted training and effective warm-up protocols.

Speed drills should exclusively involve movements that are meticulously controlled in terms of sports technique.

Speed training can be categorized into elementary speed training, employing specialized exercises with reduced resistance, and complex speed training, conducted at maximum or supra-maximum intensity levels.

To enhance reaction speed, incorporating light games with minimal reaction times is recommended, ideally tailored to the specific demands of the sport.

Training for action speed should follow a structured approach, emphasizing a high volume of repetitions and intensity.

For acyclic speed activities like jumping, focus primarily on training the stretch-shortening cycle of the muscles, endeavoring to simulate optimal conditions.

Frequency speed training may encompass general exercises such as one-legged or wide-legged hopping and jumping, typically comprising 10 to 15 exercises lasting approximately 4 to 6 seconds each, interspersed with 2 to 3-minute rest intervals.

In the context of cyclical skills such as sprinting, speed training can be divided into two facets: acceleration ability and locomotor speed.

Acceleration training should feature low-volume loading, involving minimal repetitions and sets.

Movements are executed from a state of rest and/or against resistance.

Test training should be conducted with maximum intensity, incorporating elements such as sprinting with a braking parachute or against resistance provided by car tires, or in natural environments like uphill sprints or on soft sand.

Training for locomotor speed focuses on sustaining maximum speed, necessitating high intensity and exercise durations ranging from 5 to 15 seconds, depending on the athlete’s phase of development.

Hope I could help. If you enjoyed the article or if you have any questions or comments please let me know down below.

Nick

![Read more about the article Everything you need to know about Endurance Training [Ultimate Fitness Series Part 2]](https://mensground.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/lucas-favre-JnoNcfFwrNA-unsplash-min-768x538.jpg)

![Read more about the article Everything you need to know about Flexibilty Training [Ultimate Fitness Series Part 3]](https://mensground.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/abigail-keenan-YMVGhdhEgLY-unsplash-min-768x512.jpg)

![Read more about the article Everything you need to know about Strength Training [Ultimate Fitness Series Part 1]](https://mensground.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/anastase-maragos-9dzWZQWZMdE-unsplash-min-768x512.jpg)